The EVs will kill the power grid. Or will they?

With the growing number of electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids on the streets, some people have expressed concern about how increased adoption of such vehicles might impact the energy grid. This article lists the main claims regarding the subject, and then addresses them.

The main question seems to be whether the electric grid can keep up with rising demand since experts project EVs will make up 58% of global vehicle sales by 2040, compared to 10% today. The most pessimistic prognosis looks something like this - if we take the UK as an example, there were 32,697,000 cars at the end of 2020, according to the Department for Transport. If all of them were battery-powered and charging at the same time at a typical home charger rate of 7kW, they would need 229GW of power - more than twice the country’s current grid capacity of 101GW.

The grid just can’t handle all of the EVs that are coming!

Let us put you at ease right away - yes, the energy grids can handle the extra load from EVs. Calculations like those shown above are based on faulty assumptions and needlessly alarmist. The example above is actually impossible to replicate in real life. For one, it assumes mass EV adoption overnight.

That’s simply not going to happen for a bunch of reasons but first and foremost, ramping up production of EVs can't possibly happen at that sort of pace. Second, not every single person in the world (or any specific country) will switch to an EV at the same time. That just makes no sense - people will generally keep their existing cars for a few years as they normally do, and then their next purchase may be an EV. And since not everyone has bought their current ICE car at the same time they won’t all replace those with EVs at the same time, even if there was enough EV production capacity in the world for that, which there isn’t.

They’ll all charge at the same time!

The “skeptical” viewpoint also presumes that those electric vehicles will all always charge at the same time, which is hardly possible. First, because there won’t be actual demand for that from owners, and second, because there just won’t be enough chargers around for that - at least not for a while, during which time the grid can adjust its production capacity.

By the same logic, if every Briton turned on their washing machine at the same time, they’d require around 51.4 GW of power, a value well over the average daily demand of 30 GW - and that’s the entire average power consumption in the UK in a full day, of which obviously washing machines are just a small part.

But cars are driven a lot and EVs need a lot of power!

If we wanted to be more realistic, we would need to examine the average distance cars travel and the average consumption of an EV. On average, cars in Britain were driven around 6,500 miles in 2019. To simplify the calculation, let’s say the median EV consumption is 0.346 kWh per mile. That will make the yearly consumption per car in the UK 2,249 kWh if we imagine all the vehicles in Britain are electric. Multiplying that figure by the overall number of cars gets us an answer of 73.5 TWh per year of energy necessary to power every car in the UK. That amounts to around 22% of the country's electricity generation for 2019. 22% additional grid capacity certainly paints a different picture than 200%.

Choosing another country or region delivers similar results. For instance, in the European Union, the average distance a car was driven in 2019 is 11,300km (or approximately 7,021 miles). If we accept the premise that all cars in the EU have turned electric and consume on average 0.346 kWh per mile, that puts yearly consumption at 2,429 kWh per car. Multiplying that number by the total amount of passenger cars in the region puts us at 589.5 TWh or roughly 21% of generated electrical power.

In the United States, the numbers are slightly higher due to greater travel distances, but still not alarming. Americans drove a little over 14,000 miles, on average, in 2019, per car, which brings the average EV consumption to around 4,844kWh per car per year in our imagined scenario where all vehicles are electric—multiplying that by the number of vehicles in operation totals 1,354.4TWh or 33% of the total grid production. This is consistent with the 30% increased electricity production popular YouTube channel Engineering Explained calculated was needed if all gasoline-powered vehicles in the US suddenly turned electric.

There just isn’t enough power to go around!

None of the available data gives us a real cause for concern. The last decade has been a period of lowering demand for electricity thanks to the popularization of more efficient consumer electronics, the decline of industrial production, etc. In the 2010s, generated electricity has decreased by 3% in the United States and by a whopping 18% in Great Britain.

Additionally, let’s not forget that once EVs become widespread, demand for vehicles with internal combustion engines will fall. In turn that will affect gasoline production, contributing to the trend of lowering electricity consumption in industrial production overall. Thus, freed-up electricity from any industrial sector could be used to power those EVs instead.

Ramping up electricity production to match demand is impossible!

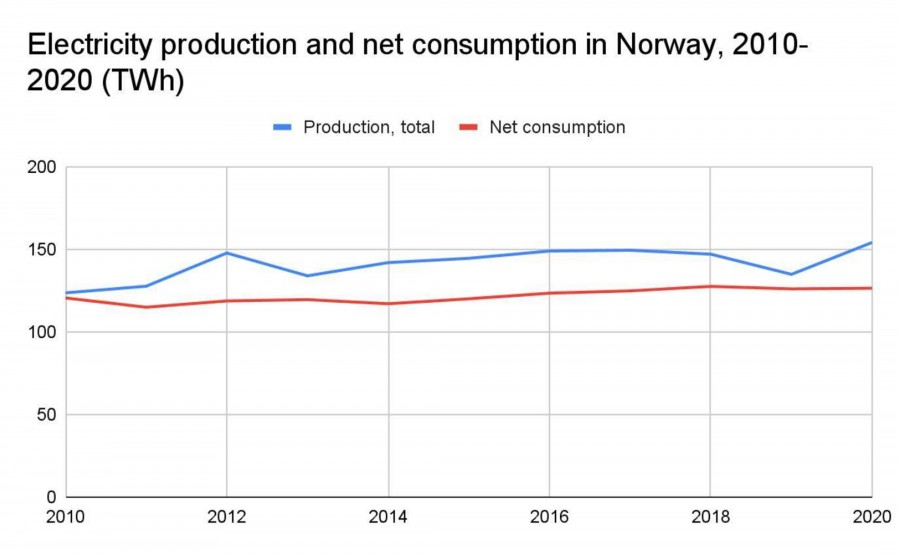

In fact, ramping up electricity production is in the realm of possibility even without radical innovations in the sector. Norway is an excellent example of this. The Nordic country is among the most advanced in EV adoption - 12% of its vehicles are now electric. Norway seems to have handled the increased need for electricity without any hiccups. Since 1990 consumption has increased by 26%, but production has been able to meet demand, as shown in the chart below.

Source: Statistics Norway

Source: Statistics Norway

The gradual adoption rate is another significant reason people shouldn’t be concerned about whether the electrical grids can handle EVs. Opposite to our theoretical examples, we can’t wave a magic wand and turn all vehicles electric on the spot. In the last 10 years, EV sales have skyrocketed. In the UK alone, registered electric passenger cars have jumped from 1,544 in 2010 to 314,966 in Q3 of 2021, an increase of almost 5000% which sounds incredible but look at the base number - that growth started at just 1,544 vehicles, and 314,966 are still a drop in the bucket.

Experts predict continued accelerated rates of adoption in the near future. For instance, EY and Eurelectric anticipate that the European vehicle park will reach 65 million electric vehicles by 2030 and 130 million by 2035 (but in 2019 the total vehicle park for the EU is 242 million, so even if that number stays the same, EVs will only make up 53% of vehicles on the road). Compared to today’s meager 3.2 million EVs on European roads, that is an increase of more than 2,000% and 4,000%, and yet, in this scenario we’d still be very far from every car on the road being an EV. Unsurprisingly then, the cited report concludes that the grid won’t collapse and will successfully cope even with the predicted mass increase in the number of EVs.

As for the States, U.S. Drive conducted an insightful study that compares vehicles to different electrical appliances according to their relative adoption speeds, thus assuming three scenarios for EV adoption - low, medium, and high. In all three scenarios, they concluded that the US grid could handle new demand as it has dealt with similar challenges in the past.

Peak consumption will skyrocket!

All of this doesn’t mean there aren’t any problems with the projected increased demand for electricity due to mass EV adoption. The biggest worry is the same as with other consumer electronics, namely overloading the grid during peak hours. Unmanaged charging could directly affect the quality of the power supply and lead to voltage fluctuations and power losses.

Electricity distributors will need to invest in higher capacity at the “last mile” and especially higher peak capacity, but they could also incentivize consumers to charge outside of peak hours by lowering costs, say, in the middle of the night. This is already done in many countries with cheaper nightly rates but could be further enhanced to entice EV users in particular.

Another solution is the further integration of smart grids, which will improve the efficiency of energy infrastructure and introduce better ways to deal with peak-time demand. Connected to that is the idea for vehicle-to-grid solutions (V2G) that could be introduced in the future. V2G is a technology that enables car batteries to charge the grid if the power demand is too great.

Obviously, this can’t happen in today’s world since V2G poses many problems. Among them is the further depletion of the Li-Ion batteries in vehicles by forcing additional cycles on them. There’s also the issue of people generally wanting to buy EVs to be able to use them as EVs, and not grid-enhancing batteries. However, such a solution could be used in combination with smart grid technology, especially in a closed system, e.g., a green-powered home in which an EV could play an integral part as a source of power in emergencies or during nighttime.

Everything's moving so fast!

In the end, everything points to the grid being able to deal with EVs just fine, given the gradual nature of the increase in adoption (and it’s still gradual even if the most optimistic assessments turn out to be true). Furthermore, study after study has shown the effect of mass electric vehicle adoption on the grid is more than manageable.

Let’s not forget we have had to deal with similar challenges to existing electrical infrastructure in the past with the adoption of the numerous electrical appliances we can’t live without in today’s world. A century ago the average consumer didn’t use electricity for much more than turning on the lights, and now we are more and more reliant on it for work, leisure and, of course, travel.

Sometimes it can feel like EV adoption might be moving too fast, way faster than adoption of any of those appliances ever did, but that happened in the 20th century, and we’re not there anymore. Wind power, solar, smart grids, batteries - none of these things were available when the appliance revolution happened, and they are now.

So let’s all collectively take a deep breath and stop worrying about catastrophes that won’t happen. And maybe, *just maybe* - enjoy all of the advantages that EVs give us over ICE cars without living in a constant state of anxiety over “what this means for the grid” or some such thing.

TL;DR

There are many challenges standing in the way of widespread EV adoption, but electricity production and the power grid are not among them.

Photo source: Unsplash

Reader comments

- Anonymous

- YT8

no matter in which century you're the past and present will affects the future. it's upto present people to live/build a better place for future generation. doesn't matter which technologies to go with nor their pros n cons. righ...

- RUA

- L66

Forcing and taking over the production of classic cars is an anti-civic action. Modern cars that meet high emission classes shouldnt be subject to the ban. Officials, politicians just like in the communist in USSR, decide almost about everything. ...

- regulated monopolies

- qyn

Utility companies are regulated monopolies. With little or poor oversite, they become inefficient or corrupt. Expect the utilities to continuously and repeatedly use every excuse to apply and rationalize rate increases.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

RSS

Settings

Log in I forgot my password Sign up